My Story

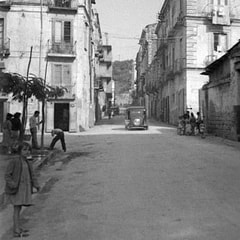

I was born in 1956, the son of a blacksmith and shipyard worker and grew up in the city of Castellammare di Stabia on the outskirts of Napoli. As many southern Italians, my family also experienced great precariousness and difficulty, often associated with lack of food.

My father, Giovanni, had a deep love of music and had studied violin, becoming quite accomplished at a young age. He dreamed of having a music career, but war and poverty were barriers he could not overcome.

In spite of the hardships we faced at that time, my father hoped I could become a musician and started to teach me solfege.

my first piano

my first piano

At an early age, he also introduced me to his violin teacher, Gennaro Calafati, and years later I would study trumpet under his son Pietro Calafati.

At the age of six, as my interest in music grew, my father bought a piano on credit, literally mortgaging the family’s financial future.

By any rational standard, the purchase was outrageous, as the piano payments were more than the rent on our home. It was an act of love and faith, which at times led my family to face great difficulties. I have kept this beautiful and precious instrument, so jealously, as it represents the love and sacrifices of my family.

I studied music with my father until I met my first teacher, the pianist and padagogue, Tita Parisi. She took me under her guidance and from that moment the most incredible chapter of my life started.

Tita Parisi, together with her husband, had become my second family.

She was a teacher who, to make sure I studied correctly, often hosted me at her house for days, in a room with a piano. Her house had truly become my home.

Under her preparation, I entered the Conservatorio di Musica San Pietro a Majella in Napoli at the age of seven. Over the next 17 years, I studied piano, organ, Gregorian music, violin, composition, choral music, choral conducting, history of theatre, opera and conducting.

At the age of six, as my interest in music grew, my father bought a piano on credit, literally mortgaging the family’s financial future.

By any rational standard, the purchase was outrageous, as the piano payments were more than the rent on our home. It was an act of love and faith, which at times led my family to face great difficulties. I have kept this beautiful and precious instrument, so jealously, as it represents the love and sacrifices of my family.

I studied music with my father until I met my first teacher, the pianist and padagogue, Tita Parisi. She took me under her guidance and from that moment the most incredible chapter of my life started.

Tita Parisi, together with her husband, had become my second family.

She was a teacher who, to make sure I studied correctly, often hosted me at her house for days, in a room with a piano. Her house had truly become my home.

Under her preparation, I entered the Conservatorio di Musica San Pietro a Majella in Napoli at the age of seven. Over the next 17 years, I studied piano, organ, Gregorian music, violin, composition, choral music, choral conducting, history of theatre, opera and conducting.

Maestro Aladino Di Martino

Maestro Aladino Di Martino

Immersed in the Conservatorio and the deep music tradition of Naples, I was guided by magnificent teachers: the violinist Alberico Valente, first chair of the San Carlo Opera; the writer and poet Vittorio Viviani, the son of the great playwright Raffaele Viviani; the composer and conductor Aladino Di Martino, who was the Director of the Conservatorio and ultimately, Ugo Rápalo, Director at the San Carlo Opera.

M° Di Martino had a musical preparation that, today, can only be found in the very few remaining musicians of the last generation. His kindness and humbleness were combined with high moral values.

Maestro Ugo Rápalo

Maestro Ugo Rápalo

M° Rápalo, whose teacher was the composer Francesco Cilea, became a special presence who profoundly influenced my life and shaped my musical career.

Along with instructing me in Opera and orchestral conducting, he begun instructing me in the transcription of 18th century manuscripts of The Neapolitan School of Music. My first transcription was a cello concerto by Leonardo Leo.

I was his student for many years and always present at his rehearsal at the San Carlo Opera House, where I heard renown singers.

M° Rápalo was himself a disciple and continuator of the Neapolitan school. Among many works, he revised and published are “La Gazzetta” of Rossini, Symphonies of Cimarosa and Piccinni and Concertos of Leonardo Leo.

In my exploration of the Conservatorio archives, I became aware that the complete understanding of the music could not be found within the four corners of a manuscript or score but in the Partimenti, the secrets of Neapolitan Masters.

M° Rápalo lead me to understand the complex difference between what he called a literal translation or revisione critica – which is a literal account of musical prediction, resulting in an especially problematic, incomplete or dysfunctional polyphonic structure. And a “truthful” transcription, which is instead a reconstruction of all the elements that had been deliberately removed by the Masters, when they were certain that the student no longer needed written information.

Along with instructing me in Opera and orchestral conducting, he begun instructing me in the transcription of 18th century manuscripts of The Neapolitan School of Music. My first transcription was a cello concerto by Leonardo Leo.

I was his student for many years and always present at his rehearsal at the San Carlo Opera House, where I heard renown singers.

M° Rápalo was himself a disciple and continuator of the Neapolitan school. Among many works, he revised and published are “La Gazzetta” of Rossini, Symphonies of Cimarosa and Piccinni and Concertos of Leonardo Leo.

In my exploration of the Conservatorio archives, I became aware that the complete understanding of the music could not be found within the four corners of a manuscript or score but in the Partimenti, the secrets of Neapolitan Masters.

M° Rápalo lead me to understand the complex difference between what he called a literal translation or revisione critica – which is a literal account of musical prediction, resulting in an especially problematic, incomplete or dysfunctional polyphonic structure. And a “truthful” transcription, which is instead a reconstruction of all the elements that had been deliberately removed by the Masters, when they were certain that the student no longer needed written information.

Maestro Bernhard Conz

Maestro Bernhard Conz

I left the Conservatorio in 1980, and after being accepted at the Hochschule Mozarteum in Salzburg, I studied Oratorio and Choral conducting with Kurt Prestel and Orchestra conducting with Bernhard Conz.

I have so many beautiful memories of Maestro Prestel who was an incredible teacher and a wonderful gentleman and Maestro Conz, an old-style Master with and unbelievable knowledge and intimidating presence.

I have so many beautiful memories of Maestro Prestel who was an incredible teacher and a wonderful gentleman and Maestro Conz, an old-style Master with and unbelievable knowledge and intimidating presence.

Maestro Herbert von Karajan

Maestro Herbert von Karajan

Then I had the privilege to audition for Maestro Herbert von Karajan, becoming one of the last students. I found him an intimidating leader,

I spent about two years in Salzburg before for I departed for Germany in 1983.

I was fortunate to spend several years traveling around Europe, performing in Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark, Switzerland, Spain, Germany and Italy.

As I grew as musician, my vision and choices changed as well as my expectations.

I am aware, therefore disconnected from the attachment to a literal style, which limits a true musical expression, reducing it to a mere routine, thus resulting in a standardized and inferior version of the musical imagination.

This awareness led me to consider the meaning of being an instrumentalist, or a conductor, and these definitions, in the specific, are very unappealing and very far away from my vision.

These mechanical actions, full of indoctrinated elements, have nothing to do with music.

Music, as a creative act, knows neither memory nor science... it does not accept conditions outside of itself. That's why it's free.

I see myself as a musician, and I express my vision through an instrument or in collaboration with others - an orchestra.

My father passed on his love for music to me from his heart; a commitment to love and the transcendent power of art, which I still strive to honor through whatever form this expression may take.

I spent about two years in Salzburg before for I departed for Germany in 1983.

I was fortunate to spend several years traveling around Europe, performing in Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark, Switzerland, Spain, Germany and Italy.

As I grew as musician, my vision and choices changed as well as my expectations.

I am aware, therefore disconnected from the attachment to a literal style, which limits a true musical expression, reducing it to a mere routine, thus resulting in a standardized and inferior version of the musical imagination.

This awareness led me to consider the meaning of being an instrumentalist, or a conductor, and these definitions, in the specific, are very unappealing and very far away from my vision.

These mechanical actions, full of indoctrinated elements, have nothing to do with music.

Music, as a creative act, knows neither memory nor science... it does not accept conditions outside of itself. That's why it's free.

I see myself as a musician, and I express my vision through an instrument or in collaboration with others - an orchestra.

My father passed on his love for music to me from his heart; a commitment to love and the transcendent power of art, which I still strive to honor through whatever form this expression may take.